Logic of Volitional Statements

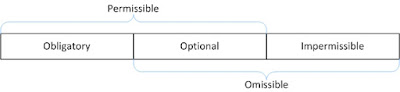

In the context of a parent's speech to a child, or any context expressing volition, there are three basic categories of speech. This image lays it out nicely:

A statement can be obligatory, optional, or impermissible. The source of this image (https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/logic-deontic/) goes on to say that "all propositions are divided into three jointly exhaustive and mutually exclusive classes: every proposition is obligatory, optional, or impermissible, but no proposition falls into more than one of these three categories." These three are mutually exclusive and cover every possibility. Since that assumes the presence of an assertion in the first place, we need to add one more possibility: silence. A parent could say nothing.

Thus we have four mutually exclusive and jointly exhaustive types of instruction:

A statement can be obligatory, optional, or impermissible. The source of this image (https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/logic-deontic/) goes on to say that "all propositions are divided into three jointly exhaustive and mutually exclusive classes: every proposition is obligatory, optional, or impermissible, but no proposition falls into more than one of these three categories." These three are mutually exclusive and cover every possibility. Since that assumes the presence of an assertion in the first place, we need to add one more possibility: silence. A parent could say nothing.

Thus we have four mutually exclusive and jointly exhaustive types of instruction:

- "You shall..." (obligatory/command)

- "If you want, you may..." (optional)1

- "You shall not..." (impermissible/prohibition)

- Silence

Notice how the optional type of statement is effectively deferring to the child's will: "if you want..." This indicates the lack of strong opinion on the part of the parent. Both command and prohibition express a strong statement, whereas the optional statement type simply defers the decision to another.

The value of an action is a separate category, which is simply either good or bad. When comparing the value of actions against each other, we have the familiar spectrum:

The value of an action is a separate category, which is simply either good or bad. When comparing the value of actions against each other, we have the familiar spectrum:

- Best (most beneficial)

- Better (beneficial)

- Good

- Bad

- Worse (detrimental)

- Worst (most detrimental)

The value judgment of an action as beneficial, useful, or profitable is an assertion of goodness. Such an assertion, however, says nothing about the oughtness of the act. Value and oughtness are separate categories. An act can be obligatory and good, or, if the law-giver is himself bad, an act could be obligatory and bad. Likewise all the possible combinations of good/bad and optional/impermissible.

Now, let's employ these categories. Starting from the state of silence, and without any contextual assumptions, it would be fallacious to assert that silence implies either command or prohibition. If a child is in doubt concerning the oughtness of an act which the parent has been previously silent, the child can ask. In this instance, the parent has the choice of instructing the act as one of our three: obligatory, optional, or impermissible. If the parent responds that the act is beneficial, a judgment of goodness, that does not, in fact, answer the question as to the act's oughtness.

If there is no room for follow up, we must conclude that the parent views the act as optional. This is because the three choices vary in the strength of volition, since both commands and prohibitions are strong statements, whereas the optional statement is not. If the parent abstains from issuing a strong statement of either command or prohibition when given the opportunity, it reveals aloofness concerning the act, and thus it is optional.

If there is room for follow up, the child would ask whether the act is obligatory or optional. A prohibition is clearly ruled out. If the response is, "You may if you want to," we know the parent views the act as optional, not obligatory.

I said above that silence does not imply either command or prohibition. However, in certain cases, there may be contextual assumptions which do allow for such an implication. If the canon of law is closed, such that no more volitional statements can be made, then silence on a matter within the canon (apart from good and necessary consequence) implies it is optional. In another case, a set of laws may, in its introduction for example, state that it uses the positive format, which means if something is not positively commanded or permitted, the silence implies prohibition. This would be something like totalitarian rule, where you may not do anything unless I say you may. If we are only looking at a portion of the canon or body of teaching, and there is silence on a matter, we cannot conclude anything until we have searched the entire canon.

Thus we should keep clear in our minds these four exhaustive and exclusive terms: silence, command, option, and prohibition. And, we should remember that a value judgment of an action as good or bad, or beneficial, is categorically different from oughtness. Use of these categories in discussion and daily life is not only obligatory for clear communication, but it is also beneficial.

I said above that silence does not imply either command or prohibition. However, in certain cases, there may be contextual assumptions which do allow for such an implication. If the canon of law is closed, such that no more volitional statements can be made, then silence on a matter within the canon (apart from good and necessary consequence) implies it is optional. In another case, a set of laws may, in its introduction for example, state that it uses the positive format, which means if something is not positively commanded or permitted, the silence implies prohibition. This would be something like totalitarian rule, where you may not do anything unless I say you may. If we are only looking at a portion of the canon or body of teaching, and there is silence on a matter, we cannot conclude anything until we have searched the entire canon.

Thus we should keep clear in our minds these four exhaustive and exclusive terms: silence, command, option, and prohibition. And, we should remember that a value judgment of an action as good or bad, or beneficial, is categorically different from oughtness. Use of these categories in discussion and daily life is not only obligatory for clear communication, but it is also beneficial.

1 I recognize that I am conflating permissible with optional in the language of "you may." Strictly speaking, as shown in the image, permissible spans both obligatory and optional. "You may, or you may not" is how to properly express optional. However, my usage here is acceptable since in practice "you may" is never understood as obligatory.